Worlding Euroculture: a guide

May 2023 | Student Assistantship: Worlding Euroculture Project

Theory: Setting Worlding Apart

Writers on worlding aim to distinguish it both theoretically and practically from other concepts that may be similar at first glance, but at their core are distinct from what worlding entails. Connery & Wilson (2007) discuss worlding in the context of (US) hegemony and imperialism, however, their book contributes to the discussion more broadly by distinguishing worlding from globalisation – a term that could be, and sometimes is, mistaken for a synonym. Globalisation is understood by the authors as a homogenising model, rooted in capitalism and (invisible) Western hegemony and privilege. It relates to market economies, the survival of the fittest, polarisation, and commodification. Worlding, on the other hand, is a model or pedagogy intended to deal with the changing world, but subvert these 'global' expectations: instead, the focus is on respect and exchange, seeking alternatives to capitalist (imperial) thought and developing a new language for future thinking, writing, and teaching. Importantly, worlding can be understood as a global (but not globalised) concept that challenges assumptions even within seemingly progressive 'takes' like transnationalism or cosmopolitanism, that do not always contest, for example, the centrality of the nation-state. It is a lens through which to interrupt and challenge assumptions. Ong (2011) corroborates this in her work on worlding Asia’s cities, writing that investigations in the field of social sciences tend to lean too heavily on two dominant approaches. One of these is globalisation and its political economy, which tends to reduce and flatten contexts to their capitalist significance. While globalisation theories seek to standardise or universalise, Ong argues that worlding practices instead “attempt to establish or break established horizons” of a given standard, in and beyond a given situation (2004, 11).

This also applies to the second dominant approach that Ong critiques, postcolonialism, and the subaltern agency at its focus. The postcolonial perspective operates on generalising tendencies, and characterises cities (as in the context of Ong’s research) outside the Euro-American region as animated only by subaltern resistance to various dominations (2011, 2). Gayatri Spivak is often cited in worlding literature for her postcolonial contributions, and demonstrates a perspective important to the practice of worlding. Essentially, Spivak (1985) argues that 'worlding' considers a place or people or history as it is, in the world; its own irreducible thing. Ascribing a term like 'third world' to something like a region, for example, places it inescapably in relation or subordination to something else. From that perspective, it may be tempting to make special effort to explore and promote the 'poor, subordinated' thing, but this practice ultimately reproduces the categories or labels that should be subverted. Worlding, then, for Spivak, means taking things in their own irreducible contexts and avoiding the reproduction of narrow, hegemonic, or otherwise inappropriate categories in research and writing. It is distinct from decolonisation because it necessarily rejects the focus on the colonial relationship: the focus could reproduce Eurocentrism, for example, because it places the ‘decolonised place’ in subordinate relation to its coloniser, rather than taking a worlding perspective that would consider that place – and its people, history, legacy – in its own right.

Worlding scholars are working to create and implement new frameworks for research, writing, learning, and teaching. The value of innovation and imagination are underscored for the creation and shaping of alternative social visions or configurations – alternative worlds – that are in (continual) emergence. The essential goal of worlding is to destabilise the norm, defamiliarise the ‘natural’, and decentre the hegemon. Its goal is in part to visiblise the unquestioned and taken-for-granted structures that frame much of the dominant understanding in (social) science. Worlding entails thinking on the interconnectedness of life on Earth, human and beyond, and actively encountering (living) ‘histories’ that can inform the present and future (Haraway 2016). It means to consider context and accept the fluidity of interpretation (Descola 2010), and can be understood as an ontology that considers the reality of a changing, more connected, yet unchangingly heterogenous world (Robiadek 2016). Ultimately, Hunter (2015) offers an apt summary of both the concept and practice:

“Worlding therefore is an active process, it is not simply a result of our existence in or passive encounter with particular environments, circumstances events or places. Worlding is informed by our turning of attention to a certain experience, place or encounter and our active engagement with the materiality and context in which events and interactions occur. It is above all an embodied and enacted process consisting of an individual’s whole-person act of attending to the world.” (189-90)

Practice: Worlding Euroculture

As demonstrated by the various conceptualisations, perspectives and operationalisations of worlding in the scholarship, there are a myriad of ways to involve worlding in academia and beyond. This next section focuses on the practical ways in which worlding can be applied – both as a lens and as an active pursuit – across academic disciplines, and particularly in the context of Euroculture. Three intersecting examples are considered here: worlding geography (Müller 2021), worlding education (Taylor et al. 2021), and worlding futures (Mitchell & Chaudhury 2020).

Müller’s 2021 article focuses on worlding in the field of geography, and engages meaningfully with the role and possibilities of ‘worlding’ in broader academic settings. It discusses the downfalls of the current system, the benefits of change, and suggests three tangible and convincing solutions to ‘world’ academia. Worlding is defined by Müller as an opening up of knowledge production, an inclusion of manifold voices and languages, as decentring the Anglosphere and foregrounding multiple anywheres. In particular, Müller discusses linguistic privilege: the Anglophone and Anglo-American hegemony visible in academic writing, publishing, and knowledge production. Referring to the politics and gatekeeping of language in getting academic work published (in English, particularly by non-native speakers/writers), linguistic privilege ultimately hinders the diversity of accessible thoughts and ideas.

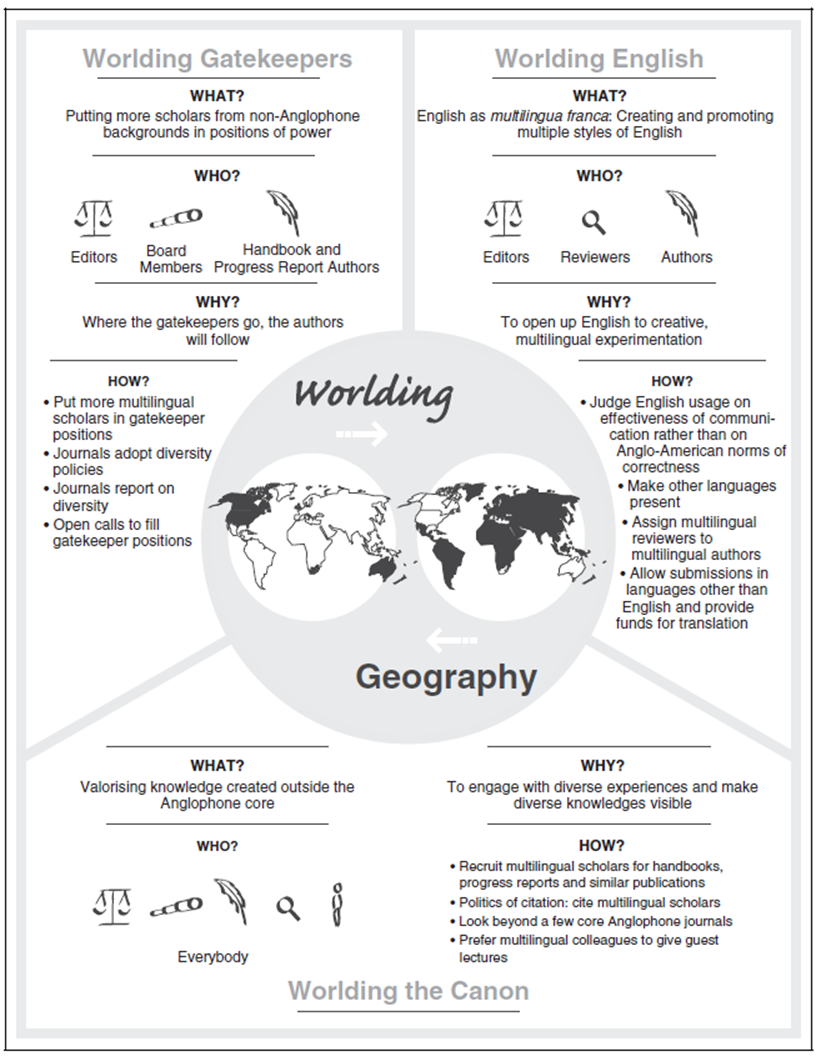

Worlding academia, in this way, challenges the notion of a ‘right kind of English,’ beyond American or British stylisations. This, worlding academia, involves three interconnected strategies. Firstly, what is designated as ‘worlding gatekeepers’: promoting those with multilingual or non-Anglophone backgrounds in position of (academic) power, such as editors and board members. Secondly, ‘worlding English’: overturning the view that academic linguistic authority belongs to native speakers only and that non-native speakers are ‘deficient’ and need to ‘catch up’; instead, Müller suggests thinking about English as a ‘multilingua franca’ with the room to challenge traditions and allow for a more inclusive, representative academic language. Thirdly, ‘worlding the canon’: acknowledging, including, and engaging with world texts, bringing them together to make up the selections and sections of knowledge that inform worlded learning from more representative perspectives. It also means, Müller emphasises, “engaging in a conscious and conscientious ‘politics of citation’” (2021, 1459); that is to say, not just citing authors who are well-known or well-cited because they are well-known, but remaining open to reading and citing upcoming, early-career, and non-anglophone researchers. Included below is a useful graphic by Müller, outlining the important questions to ask implementing these three worlding strategies (Appendix 1).

Despite the article’s focus on the disciple of geography, Müller’s strategies can also be applied, in different but meaningful ways, to the project of Worlding Euroculture. The first strategy, regarding publishing gatekeepers, is not something students and staff in the Euroculture programme have control over, however could be something to pay special attention to when searching for and selecting sources. Strategy two, worlding English, is closer to this project: being able to coherently communicate academic ideas and arguments, rather than having flawless English, could be emphasised and supported within the programme; staff and students might also be encouraged to use words, translations, and constructions from their own languages and cultures to supplement the numerous ways in which English is limiting. Finally, the strategy for worlding the canon is perfectly applicable to Euroculture. Our programme by nature is incredibly international, and encouraging students to not only search and cite more widely, but actively incorporate sources in languages other than English, is a practice of worlding that would benefit many.

Consciously setting goals for non-Anglophone citations and sharing the knowledge, whether in English or not, with others in the cohort benefits students as they broaden and deepen their academic experience, but promotes researchers marginalised in the dominant academic culture. This strategy can be expanded to cover intersections of language, ethnicity, and gender. Bringing these practices beyond individual work also to group work, the IP reader and the introductory reader would set the tone and standard for a worlded Euroculture education.

Taylor et al. (2021) writes about the application of worlding as pedagogical tool, and through the notion of ‘common worlding,’ adds an ecological consideration to worlding practices. Just as other texts have set worlding apart from globalisation or postcolonialism, the authors here explain that much of the (Western, colonial) hegemonic thinking is also individualistic and human-centric to a fault, in ways that have resulted in (cultural) genocide and ecocide across the globe. By decentring humans and reattaching them as an equal part of the environment (including flora, fauna, or weather), common worlding offers a perspective on the future that is connected, creative, and sustainable. In this way, new and alternative ways of knowing are opened up that acknowledge and engage with the Anthropocene and its consequences, rather than taking for granted the role and impact of humans in and on the world. This particular research was directed at engaging young children in the world around them, but the strategies used by the authors are expandable: employing flexible curricula that follow real-life encounters, or avoiding teaching and learning about the world as if it is fixed and that humans are separate from - rather, “thinking and learning with the worlds around us” (2021, 75).

Common worlding pedagogies consciously include ecological world views that underscore the interconnectedness on Earth, as well as responding to global and local ecological challenges. These worlding strategies could be implemented in the context of Euroculture by consciously including ecological perspectives on the global and local scales – in individual work, classroom discussions, assigned reading and readers, and as a standard part of understanding academic and research contexts. Building Euroculture beyond linguistic privilege and human-centrism can work to world the programme in a way that fosters critical thinking and wider empathy for the graduates it produces.

Finally, Mitchell & Chaudhury’s 2020 article discusses the worlding of the future, negotiating white apocalyptic visions in social sciences and BIPOC futurisms in science fictions. While ‘worlding’ is not found by name in this text, besides in the title, it gives a very clear and topical example of the process of worlding. And, beyond the process, it also highlights the necessity and benefits of moving away from a dominating power structure – in the case of their research, this structure is whiteness. However, the strategies the authors use are strongly applicable and adjacent to other power structures too, such as Eurocentrism. In other words, Mitchell & Chaudhury present what worlding can look like in practice. The article begins by rejecting Eurocentric notions of a single world or a single future; these are the blocks that build ‘the end’ of ‘the world’ and is the assumed universality that the authors intend to challenge. They follow by defining whiteness, not as a skin colour but as a “set of cultural, political, economic, normative, and subjective structures derived from Euro-centric societies and propagated through… colonization and capitalism” (2020, 311), and the hegemonic structures are those that inscribe racial differences and privileged those that are recognised or constructed as possessing ‘whiteness.’

One of the key points, and one that is visible in many of the works on dominance, hegemony, and worlding, is that this privilege “is remarkable in its ability to render itself invisible to those who possess and benefit from it,” meaning that its influence often goes undetected by those exerting it (ibid). The authors posit that those with voice, representation, and power – whether political, social or academic – are the ones that create imaginaries, create worlds, and thus it matters whose worlds are excluded or privileged. The worlding practice that Mitchell & Chaudhury engage in to combat the ‘apocalyptic visions’ of white future is to deliberately foreground what they call ‘BIPOC futurisms;’ that is, imaginaries created by Black, Indigenous, People of Colour, centring “diverse, plural subjectivities and forms of agency, undermining homogenous notions of ‘humanity’; attune to nonlinear temporalities; and embrace lively practices of mobility and hybridity” (2020, 321). Their work engages the music and science fiction of Afro-futurism; the performance arts, ceremonies, and video games of Indigenous futurisms; the rich, dynamic, and history-rooted imaginaries of Asian futurisms. In this way, the authors demonstrate and honour alternative ways of knowing, explore alternative futures, as presented by those marginalised by the hegemony.

Just as earlier definitions of worlding can be summaries as the process of destabilising the norm, defamiliarising the ‘natural’, and decentring the hegemon, Mitchell & Chaudhury offer the alternatives: recentring diversity and plurality, refamiliarising marginalised perspectives and knowledge systems, and restabilising notions of agency and sovereignty. These processes, strategies, of worlding can be brought to the Euroculture programme, too, through the deliberate foregrounding of more diverse (academic) content with the purpose of engaging with the richness that exists beyond Anglophone, white, human, or otherwise Eurocentric knowledge systems. Worlding, as is posited by this article, requires the deliberate negotiation of what words like ‘we,’ ‘humanity,’ ‘progress,’ ‘global,’ or ‘responsibility’ really refer to, considering the identifications of the writers and works cited. Worlding means continually looking out for and confronting cases in which (global) power structures like whiteness or Eurocentrism are reproduced, “at the cost of all other life forms” (2020, 325). In the context of Euroculture, recognition, education and facilitation of worlding strategies are the foundation for creating both an environment conducive to and young scholars confident in worlded research practices.

References

Connery, Christopher Leigh, and Rob Wilson, eds. The Worlding Project: Doing Cultural Studies in the Era of Globalization. Berkely: North Atlantic Books, 2007.

Descola, Philippe. ‘Cognition, Perception and Worlding’. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 35, no. 3/4 (December 2010): 334–40. https://doi.org/10.1179/030801810X12772143410287.

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Hunter, Victoria. ‘Dancing – Worlding the Beach: Revealing Connections Through Phenomenological Movement Inquiry’. In Affective Landscapes in Literature, Art and Everyday Life. Routledge, 2015.

Mitchell, Audra, and Aadita Chaudhury. ‘Worlding beyond “the” “End” of “the World”: White Apocalyptic Visions and BIPOC Futurisms’. International Relations 34, no. 3 (1 September 2020): 309–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117820948936.

Müller, Martin. ‘Worlding Geography: From Linguistic Privilege to Decolonial Anywheres’. Progress in Human Geography 45, no. 6 (1 December 2021): 1440–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520979356.

Ong, Aihwa. ‘Introduction: Worlding Cities, or the Art of Being Global’. In Worlding Cities, 1–26. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444346800.ch.

Robiadek, Katherine M. ‘Worlding versus Worldview: Heidegger’s Thinking on Art as a Critique of German Historicism’. Monatshefte 108, no. 3 (2016): 383–94.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. ‘Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism’. Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1 (October 1985): 243–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/448328.

Taylor, Affrica, Tatiana Zakharova, and Maureen Cullen. ‘Common Worlding Pedagogies: Opening Up to Learning with Worlds’. Journal of Childhood Studies, 21 December 2021, 74–88. https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs464202120425.

Appendix

Appendix 1: “Three paths of worlding Geography: worlding gatekeepers, worlding Englishes and worlding the canon” (Müller 2021, 1456).