Behind Closed Doors: care, work & citizenship in Cuarón’s Roma

January 2023 | Dimensions of Citizenship | 8.0

Introduction

The early months of 2020 marked the start of a period that would impact the globe: a pandemic breaks out, lockdowns ensue, and offices, schools and businesses shut their doors to curb the spread of Covid-19. For many it began the era of ‘work from home,’ as cars disappeared from the roads and shoppers from the streets. Something else disappeared in and after this period too, however, unnoticed though not insignificant: just in the United States, two million women disappeared from the workforce.[1] Due to the closures of schools, day care centres, and the reality of the family being always at home, mothers left their jobs in the ‘official economy’ and instead worked from home. This work, care work, is not regarded as equal to traditional productive labour in a capitalist system; rather, social reproductive labour such as child or elder care, home maintenance and emotional upkeep of a household are seen as non-market activities that do not economically contribute in the conventional sense. Further, the women who dropped out of the labour force to care-work from home are not considered employed nor as unemployed jobseekers, and are thus entirely unaccounted for in the economy.[2] Besides the extenuating circumstances of a pandemic exacerbating the problem in the last years, un(der)paid and undervalued care labour is across the globe disproportionately carried out by women; labour that, while keeping the economy running, is not counted nor compensated by the current economic system.

The paradox of care work as being socially and economically necessary yet unrecognised is not confined to the mothers or wives in a family unit, but is seen widely in feminised care industries. These industries are feminised in the sense that they are perceived as extensions of the traditional woman’s roles[3] and operate on negative assumptions of low-skilled and replaceable workforce.[4] Both outside and inside the home, social reproduction labour – like childcare and aged care, domestic or commercial cleaning, housekeeping and nannying, or any combination of these roles – is often carried out by migrant women in sectors “typically regarded as marginal and precarious.”[5] The intersections between gender, class and ethnicity become visible in the execution of paid and un(der)paid care work, as do the pitfalls and blindspots of capitalist economic systems, and the (dis)connections between citizenship and care that underlie these contentions.

Because of the private, domestic, or after-hours nature of care work, its visibilisation happens less readily in reality than it does through representation in art. Literature, including film, is always related to politics and society in that they not only shape but are shaped byeach other, as writers and directors have their personalities and worldviews influences by their social and political environments, and as politics adapts to the contemporary norms and values that are shared and often proliferated through works of literary fiction.[6] This is particularly true for works of autobiographical fiction and life writing, in which creators explicitly hold up the mirror of their own experiences and observations to their own sociopolitical contexts, as well as that of their audiences. With this paper, I investigate the interconnections between care, work, andcitizenship, as they are represented in Alfonso Cuarón’s 2018 film Roma, and the significance of gender and class in the film, through the lens of social reproduction theory and performative citizenship. This study begins with a theoretical framework exploring the concepts related to social reproduction theory and care work, intersectionality, and citizenship. A methodology section follows, providing a background on this research’s selected case study. The subsequent chapter contains the analysis and discussion of the themes and markers of Roma, and the final section concludes this essay by placing the work in context and discussing further research.

Theoretical Framework: (Re)Evaluating (Re)Production

The notion of social reproduction is constructed in complement to the concept of production as central to the capitalist system’s operation. If the core of the capitalist system is that workers produce (wealth, products, services), social reproduction theory (SRT) shifts the focus to another question: who and what (re)produces the worker? Production is the labour that creates wealth for the market, often in tangible form, and is the only form of ‘legitimate work’ under capitalism.[7] Meanwhile, the care and work that goes on – mostly behind closed doors, such as providing rest, nourishment, education – that makes productive labour possible, is not considered as valuable and is thus not fairly compensated. Bhattacharya’s 2018 edited volume Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression discusses this in various levels of detail: the relationship between oppression and exploitation in capitalism, the ‘naturalisation to nonexistence’ of socially reproductive work, the role of the ‘family’ as a site for informal productive labour.[8] Essentially, Bhattacharya argues, SRT is a methodology for studying the processes of labour and labour power under capitalism, and understanding “the variegated map of capital as a social relation.”[9] In the same volume, Hopkins writes about the relationship between SRT and care work, especially in formal, paid instances. Paid domestic labour has its own set of difficulties when it comes to the situation of the workers: they tend to be both socially and spatially isolated due to a lack of colleagues, not being unionised, and excluded from labour laws.[10] Further, live-in domestic workers find themselves in the blurred, overlapping spheres of production and reproduction.[11] Their productive labour (the reproduction of others, their employers) takes place in the same space as where their own personal reproduction should also happen, which could intensify elements of precarity in cases of labour disputes if losing a job means losing a roof too. Even when carried out in structures that are meant to be protective of the labourer, the nature of the work as reproductive instead of productive in the capitalist sense means that exploitation and irregularities in the employer-employee relationships are very likely.

It is not only the undervaluing of care work that creates and perpetuates exploitation and inequalities, but it is worthwhile to consider who carries out the care work. An intersectional approach, or the consideration of intersectionality in these cases, plays a role in uncovering where citizens – those with the ability and authorisation to exercise both rights and responsibilities[12] – are placed in vulnerable positions with reduced agency. There are many intersections to be considered when studying the social locations of individuals and groups, such as religious affiliation, sexuality, civil status, or more.[13] For the purpose of this paper’s research, however, the intersections of gender, class and ethnicity are central to understanding the interconnections between care, work, and citizenship. Davis writes that intersectionality, as critical methodology, is well suited to the exploration of how the three mentioned intersections “are intertwined and mutually constitutive, giving centrality to questions like how race is ‘gendered’, gender ‘racialized’, and how both are linked to the continuities and transformations of social class.”[14] This is based in part on works by Nira Yuval-Davis and Floya Anthias, and Yuval-Davis notes that centralising this ‘mutual constituting’ is important in discussions of citizenship so as not to “homogenize the differential meanings of such identity notions”[15] but rather engage meaningfully with intersections, social locations and citizenship.

The social, economic and political vulnerability and lessened agency that come with an exploitative work situation affect the abilities of citizens to actively perform their citizenship. Performative citizenship, as defined by Isin, comes in many forms. Essentially, in Isin’s understanding, rights constitute citizenship, and the delineation of who has access to these rights is contestable, thus citizenship can be practiced – performed – by claiming rights as well as exercising them.[16] There are many ways to perform citizenship in this context, and of the examples Isin discusses, many of them entail group formation (as a protest, action group, social movement, solidarity organisation) based on some shared identity or element of intersection – be that locality, ethnicity, legal status, sexuality, employment situation, or another ‘thing in common.’ Thus, these performances of citizenship can be considered dependant, at least in part, on the security and agency of the citizen; that the one (attempting to or in need of) claiming rights is safe to do so and physically, emotionally, and financially able. As discussed, individuals or intersectional groups of individuals that are overrepresented in exploitative and irregular care work settings tend to be in vulnerable positions with reduced agency, which consequently can impact their capacities for performing citizenship. This is especially true in paid domestic work because, as discussed, these workers tend to be relegated at the margins of society regarding (their intersectional positioning of) gender, class and ethnicity; are not privy to colleagues, unions and all legal protections; and due to overlapping spheres of work and life, live-in workers risk their shelter in rights confrontation. Furthermore, care work and domestic labour are often consigned to the ‘private sphere:’ Pratesi problematises this when she argues that defining “care as a private concern—combined with the gendered division of labour—means excluding women from a series of entitlements and benefits” and reproducing a citizenship constituted by a set of gendered social rights.[17] Despite care work and social reproduction being integral to the capitalist system in (re)producing labourers, it is just as central to democracy: this work reproduces citizens, to participate as members of social and political communities.

Methodology: SRT, Analysing Film & Why Roma

Art and fiction are keenly studied in the field of literary and cultural analysis. Scholars in the fields of social science and humanities explore the importance of negotiating the truth behind the story and what impacts fiction can have on reality: the social processing of trauma or success, the acceptance or rejection of external influences, or the public imagination of a story printed or on screen versus in the news. Utilizing the elements of SRT, intersectionality and performative citizenship as a lens through which to analyse fiction serves to reveal new interconnections, impacts, that fiction may have on reality. While the first thought of ‘literature’ tends to be written pieces, film and visual media are included as literary works for their ability and practice of carrying culturally significant meaning: films can be analysed for their symbols and messages just as any book could. Films are wildly popular forms of cultural entertainment, and the rise of streaming platforms and collaborative online upload sites means that video content is more widely available than ever before. Box-office takings were previously very much the measure of success for new releases, but contemporary success is now also measured in the number of views or streams a particular film may have. Essentially, films have always been and continue, perhaps even in a growing degree, to be locales for entertainment, information, and familiarisation with subjects for a wide range of audiences. In a similar way to other works of fiction or fact, where authors of varying backgrounds and intentions aim to explain events and explore narratives (though sometimes problematically), so film directors and writes work to tell a particular story from a certain perspective.

This is especially true for Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma: the film is a work of autobiographical fiction or form of life writing, based on the director’s own upbringing in the Colonia Roma neighbourhood of Mexico City, spanning roughly one year between 1970 and 1971. The black and white film – a purposeful nostalgic choice juxtaposed by its ultra-modern grainless resolution and extra-wide aspect ratio – has won over 250 awards since its release in 2018, including three Oscars as well as ten Ariel Awards from the Mexican Academy of Cinematographic Arts and Sciences.[18] Roma’s theatrical release encompassed over 1,100 cinemas worldwide,[19] and is available in most countries on Netflix. This is to say: Cuarón’s film has been seen and appreciated by millions, and this global engagement contributes to its value as the focus for this study.

Life writing is defined as a process of using “fictional and poetic techniques to capture self-experience, including physical and emotional experience, personal memories, and present and past relations with others”[20] which encapsulates the efforts behind Roma: the streets and sets are recreated from Cuarón’s memories, the era-appropriate furniture borrowed from local friends and family, the main characters based on Libo, Cuarón’s own childhood nanny, and the story on his own parents’ separation.[21] Life writing as a cinematic experiment allows Cuarón to process real memories, real happenings, real emotions and real places though an artistic outlet, where the stories can be adjusted to highlight new things, through the looking glass of the present on the nostalgia of the past. Besides its autobiographical (and thus historically focused) themes and popularity, I chose Roma as a case for another related reason: its poignant subject matter. While there is no true protagonist, the story is driven by what happens to Cleo, an Indigenous maid, and Sofía, the mother in the upper-middle class family Cleo works for and lives with. Particularly, the film negotiates the boundaries between work and private life for a care labourer like Cleo, the ways gender and class are addressed within the household and outside the living/workplace. Finally, the film negotiates the context of social and political unrest that backdrops the years in which the film takes place. These elements are what set Roma up to be an enriching and valuable resource in the context of this study.

A close reading of the film through the lens of social reproduction theory is combined with a focus on water. Water is a key motif in the film Roma, and its presence is woven through the film’s pivotal moments. For example, waves of soapy water from a mop-bucket lap across the screen in the film’s opening scene, and the scene in which Cleo shares her pregnancy announcement with her employer is marked by the sight and sound of rain and hail, and the steam of two cups of tea. Goh writes that in Cuarón’s Roma, “water and labour are interchangeable, and that labour is always in the hands of female characters,”[22] and for this reason the main scenes at the focus of this research’s analysis engage meaningfully with the presence and use of water. The film itself is structured in a flow, too: the long, panning shots and wide angles of the camera float gently between characters, and the focus is never too subjective. Because of this there is no true climax to the film, but rather points at which the rushing of the stream intensifies before the current calms again.

Analysis

Although the film has numerous relevant, profound, and intriguing scenes, the scope of this essay limits the analysis to three main plot points of Roma: the family’s holiday break on delicate land, Cleo’s shopping trip and labour at the hospital, and the seaside reunion that serves as part of the film’s closing scenes.

In short, the film is set in 1970s Mexico City and follows a middle-class family living in the neighbourhood of Colonia Roma. Living in the large family home is Sofía, her mostly absent husband Antonio, their four children, and Sofia’s mother Teresa. On the same property lives Cleo who, along with friend and co-worker Adela, is an Oaxacan (Indigenous) live-in maid at the family’s home. Cleo feeds everyone, cleans, does laundry and takes care of the children as part of her job, and she and Adela speak Mixtec when together (though Spanish in front of the family). When Antonio’s work trips become longer and more frequent, his infidelity and marriage problems become evident and eventually he begins moving out, leaving Sofía behind with her mother, four children and three domestic employees. Cleo falls pregnant after a Sunday afternoon date with Fermín, and he abandons her when she tells him about the situation later. When Cleo confronts him once more later in her pregnancy, Fermín denies his paternity and threatens violence against her and the child if she contacts him again. Considering the strength of the Catholic Church in Mexico at that time and the tightly controlled discourse on abortion,[23] Cleo shares her pregnancy news with Sofía and tearfully asks if she’ll be fired. Sofía hugs her reassuringly and promises that she won’t lose her job and they’ll get her checked up.

Water Shortage

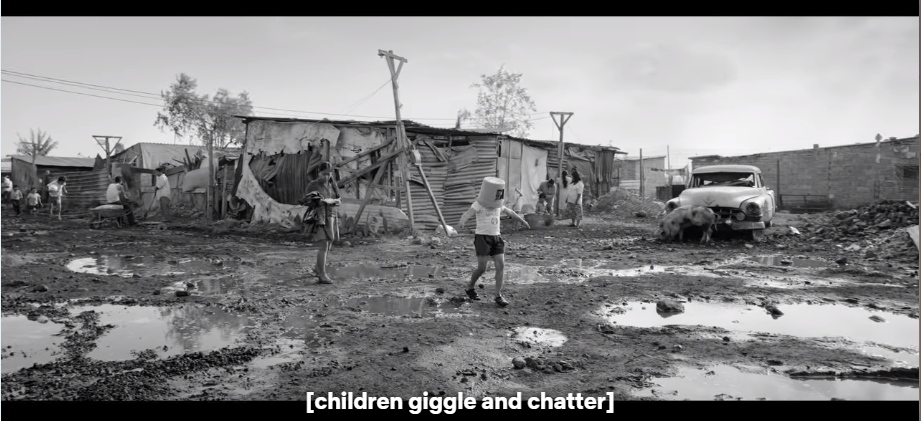

Around the middle of the film, the family (minus Antonio) travel to spend some nights at a wealthy friends’ hacienda, or estate, over the New Year holiday. The estate is complete with multiple living quarters for the adults and the children, as well as a separate downstairs ‘servants quarter’ where the domestic and physical labourers of the hosts (and those brought along by the guests) stay and celebrate the holidays after a day’s work. The spacious estate grounds contain woods and grasslands and a shooting area, and the characters hints at a tension surrounding the land: “the villagers [are] angry with Don José over the land,”[24] says Benita, the host’s housekeeper, and “in defence of our rights – united – the land” says a banner hanging outside the property (appendix 1). It is in this portion of Roma that the class and ethnicity divides are amplified, and the disparities between employer and employee are heightened. The family arrives and while the adults greet each other and the children run off to play, (pregnant) Cleo carries the family’s baggage to their respective rooms. Later, the guests are picnicking in the grassy area near the forest, and the audience is introduced to the scene with one child hopping puddles in a full astronaut costume (appendix 2) while the camera follows a group of children running towards their parents. The class privilege here is juxtaposed explicitly with a later scene, when Cleo visits a poor town outside the city and an impoverished child is playing astronaut too, though with a bucket as a hood instead of a costume (appendix 3). The women are sitting in chairs with glasses of wine while the men shoot, and the maids sit down on the picnic blankets with the kids. At one point, Sofía decides she wants to shoot too and yells back at Cleo to watch the children, as if the roles are not already clear, and walks off.

As the evening goes on, the guests drink and smoke while the children are being cared for by the maids. Benita, an old friend of Cleo, asks one of the other maids to keep an eye on Sofía’s children while she takes Cleo downstairs, outside past the dogs and chickens, for some more age-appropriate celebration with the other employees. At least, those not involved in childcare: when Cleo asks if she should call the other maids to join in celebrating the New Year, Benita replies, “we don’t want those city nannies here... they feel [too fancy]”[25] and the two head into the lively party. Once inside and with a drink that Cleo at first refuses, Benita explains that the son one of the estate workers was killed earlier that year over the land dispute. Cleo goes to take a sip of the alcohol, but a dancing woman knocks her and the cup falls shattering to ground. In a study of larger scope, there would already be notable content for analysis in the symbols and foreshadowing of the chaos – both local and personal – to come in the film. More feasible for this analysis are the black, white, and grey divisions of class in these scenes and the way these intersections relate to agency and the performance of citizenship. From the outset, Cleo’s comfort in the presence of her employers is juxtaposed with her discomfort in the large ‘upstairs’ group, just as her comfort with Benita is juxtaposed with her discomfort in the large ‘downstairs’ group. The ‘grey’ space between classes that Cleo inhabits demonstrates the divides, acting as an insight into the social reproduction and care work that happens, even on holidays.

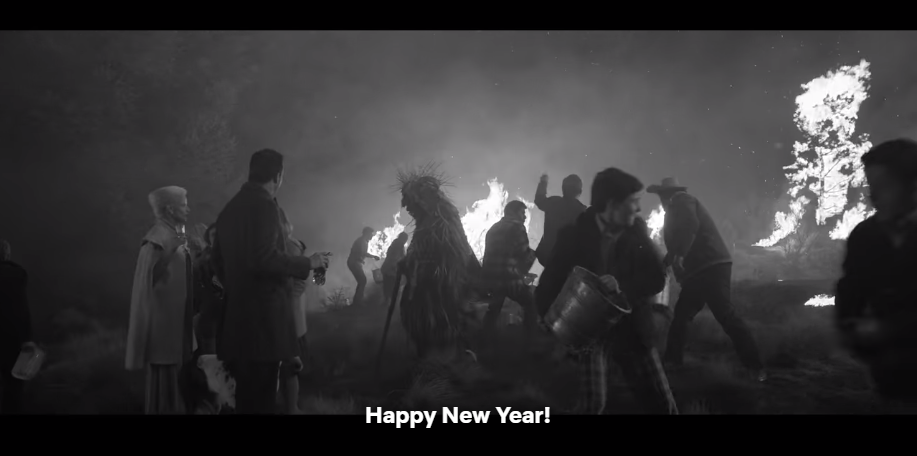

The audience watches as Cleo heads back upstairs but pauses at the balcony when she sees sparks and flames over the trees – a few moments later the attendants of the downstairs party come shouting about the fire in the woods, mobilise to make a water bucket chain and rush to stop the spread. It is implied but not discussed that the fire was set deliberately in correlation to the property tensions.[26] The guests of the upstairs party rush out too, the children with little watering cans and the adults with glasses of wine, to witness the spectacle (appendix 4). This all happens against the backdrop of the countdown: ten seconds left in 1970, with the competing sounds of crackling fire and cracking fireworks to welcome in 1971. The water keeps coming and the flames keep burning, but the challenge is so much larger the buckets of water and their carriers could hope to address.

Water Spilled

Three quarters of the way through Roma, the audience meets Cleo a few months later, in June 1971, as she is heavily pregnant. Teresa, Sofía’s mother, takes Cleo shopping for furniture: “…my maid needs a crib,”[27] Teresa says to the store employee, and they walk through the store. In these few short moments, a number of notable factors are at play in the blurry employee-employer relationship. First, the scene is a reminder of the seemingly irregular responsibilities shared between the two: in very few other employment situations would it be normal for a boss to take their staff shopping for baby necessities, let alone organise and accompany them to medical check-ups regarding pregnancy. Second, Teresa refers to Cleo as ‘my maid,’ despite Cleo being employed not by her but by Sofía: in few if any other situations would an employer’s parent describe you as their own employee. Finally, despite going out to buy furniture for Cleo, the audience is experiencing a gap perhaps left intentionally by Cuarón as foreshadowing, or perhaps unintentionally so as not to have to think about that part of his childhood, in that there has been no discussion on where or how the living arrangements in the family home will change to accommodate Cleo and an infant. At this point, the audience knows that the all bed- and study rooms in the house are occupied, the children sleep two a room, and the detached living space where Cleo and Adela sleep isn’t even big enough for two beds and an ironing board, let alone a crib and another fussy human.

All this serves to remind the audience that the care worker relationship with those Cleo is caring for is complex: she is like family in many senses, being cared for too. Throughout the film, this family-like relationship is evident in moments like when the children tell Cleo they love her, when Sofía turns to Cleo for emotional support, or when they all watch television together after dinner. However, in those same times, Cleo is clearly not actually family: she sits on the floor to watch evening programmes, is sent to make tea after emotional moments or smoothies for the children who love her. She is supported in her pregnancy, but is still ‘my maid’ and not Cleo.

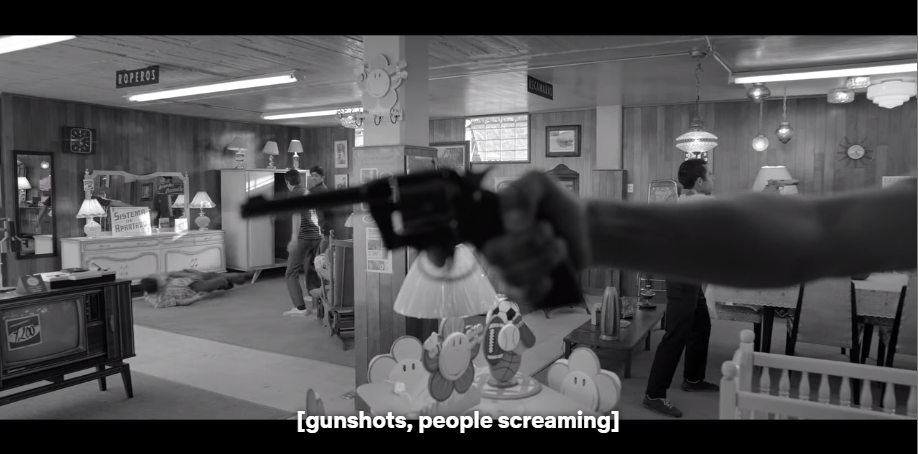

This ‘like family’ but not family motif is most clear in the minutes following the scene in the furniture store. The day of the shopping trip, June 10th 1971, would later be known as the Corpus Christi Massacre: protesting students across Mexico City were gunned and beaten down by Los Halcones. This para-militant group of men allegedly was trained and armed by the Mexican government to “carry out the dirty work of supressing the student movement,”[28] and the ensuing violence – as well as the police’s non-interference – plays out in the background of the shopping trip in Roma. Cleo and Teresa must walk far from the car to the store because of the student protests, and there are police and picketers scattered throughout the streets. The setting of social and political unrest here, just as with the fire over New Year’s Eve, is cinematically observed as spectacle until the moment two students are chased into the store by four Halcones, and the camera freezes on a gun pointed at Teresa and Cleo (appendix 5). A student is shot in the background, and the camera pans to show Fermín, the father of Cleo’s baby, holding the gun. The four men run out again as they came in and as people are screaming and calling for help, Cleo’s water breaks. The recurring motif of water here signals the pivotal nature of this point in the film. Stressfully, they head towards the hospital and Teresa holds Cleo as she goes into painful labour in the backseat of the car, but the chaotic traffic means it takes them over two hours to get there. By the time they arrive, Cleo can barely stand and Teresa is incredibly flustered. As the former is wheeled off to delivery, the reception asks Teresa for patient information:

Nurse: What’s her full name?

Teresa: Cleodegaria Gutiérrez.

Nurse: Her middle name?

Teresa: I don’t know.

Nurse: How old is she?

Teresa: I don’t know.

Nurse: Her date of birth?

Teresa: [crying].

Nurse: What’s your relationship with the patient?

Teresa: I’m her employer.

Nurse: Is there any family member here?

Teresa: No. No.

(Cuarón 2018, 1:38:33 – 1:39:21)

Here the audience is reminded without a doubt that no matter how much Cleo does for the family, Teresa included, how close they get or how much they say she’s like family, there were no family members in the hospital with her that day. Cleo is a ‘city nanny,’ far from her own mother and her village, without the care that a truly reciprocal (family, blood or chosen) relationship would offer. The broken water is symbolic of broken relationships: not only between Cleo and Fermín, but the mismatch, the class divide, between employer and employee. In few other situations would an employer be expected to know a staff member’s middle name or birthday off the top of their head.

Water Abundant

In the final twenty minutes of the film, the audience is offered the closure of a chapter and insight into the inner worlds of Cleo and of Sofía. By this point Cleo has returned home from the hospital after the stillbirth of her daughter, and is silently grieving alone. Sofía has accepted that her husband won’t be coming back anymore so she begins preparing for him to move out. She tells the children that they’re all going on a small vacation to the beach, and invites Cleo to come too in an attempt to life her spirits – Cleo declines at first, but Sofía, the children and Adela all pressure her to join and Cleo relents. Notably, Sofía states to the kids: “… but she’ll be on vacation, you can’t make her work,”[29] before they set off together to the coast. The audience learns that Cleo can’t swim and prefers to stay safely on the sand, and they check in to a holiday bungalow and go out for dinner. It’s during this dinner that Sofía tells the children that Antonio isn’t going to be living at home anymore, that the reason they’re on this vacation is to give him time to move his things out, and that she’s going to work in a new industry full-time. Sofía and almost-mute Cleo support the children through their feelings and sadness at the thought of their dad leaving the family.

In this moment, the gendered struggles that bond Sofía and Cleo despite their other divides are clear; it’s a case of same problems, different day. Both women have been let down and abandoned by the men they should’ve been able to trust, leaving them to live and work in a patriarchal system not built for their multifaceted success, regarding employment and motherhood, for example. Both have been burned and felt isolated by the expectations and perhaps even shame of living ‘outside the bounds’ of the socially acceptable: Cleo as an unmarried mother-to-be, at first, and later as a maid with no family, and Sofía as a woman scorned with no husband. Earlier in the film, after a night of presumed bad news and subsequent drinking, Sofía returns home and sloppily tells Cleo that “no matter what they say, we women are always alone.”[30] And indeed, the film’s women support each other much more than any man supports them.

Their shared gender is not enough to make these characters equal, however, and the class divides that separate the employer from the employee make their way into scenes of solidarity anyway. Despite Cleo being invited away for a (presumably unpaid) break after a medically traumatic loss, she does not get any time to rest herself. After the vacation dinner, the group get ice cream as dessert and head outside to eat – Sofía and the four children sit on the bench; Cleo stands. The kids are sunburnt from their swims earlier, and Cleo dresses the youngest and helps the others sooth their pain. The most poignant scene, however, takes place at the beach again the next day. The six of them are on the sand when Sofía announces that she needs to check the car tyres’ air pressure, and the oldest son would join her. She begins to walk away, asking over her shoulder if Cleo won’t mind just watching the kids for a while, and don’t they go into the water since Cleo can’t swim but of course if they must just stay near the shore and she’ll be right back! Sofía leaves Cleo on the sand caring for three children on her vacation, essentially doing the work she’s usually paid for, for free.

Of course, the two middle children push the limits and go further from the shore than intended while Cleo is tending to the sandied youngest. She calls and calls for them to come in closer, but eventually can’t see them any longer and so runs clothed into the water she can’t navigate. After being battered wave after wave, Cleo manages to grab both kids and make it back to shore where the three of them collapse, sobbing with fear and relief. Sofía and the other two children come running and they huddle together on the sand, crying that Cleo saved them, when Cleo breaks her silence with the emotional revelation that she “didn’t want her… didn’t want her to be born.”[31] The family and Cleo stay huddled close on the sand while Sofía repeats over and over how much they love her (appendix 6), as the water laps ever closer at their knees.

Discussion: Care Work & Citizenship

In each of these analyses, three themes are recurring: the role of gender in setting up the struggle of care work, the struggle’s intersection with class and ethnicity to add complexity and difficulty, and the way in which ‘family’ ties complicate the relationship between worker and worker-for. These three themes relate closely also to citizenship in that in each case, the characters are made vulnerable, and their agency is stripped, impeding their capacities for performing citizenship.

Cleo and Sofia meet on the level of gender: both struggle with the realistic prospect of single motherhood, operating within a patriarchal society that relegates them to the side lines and makes them fight for their agency. Their ‘work’ is not compatible with their ‘lifestyles’ if men are not involved. When Antonio leaves, Sofia must work again to afford the reproduction of her children via paying for maids, who become even more necessary than before due to her forthcoming absence. When Cleo becomes pregnant and there is no father involved, there is an omission – as allowed for by life writing – about what her future really looks like, whether she can realistically keep working or what would actually happen if she brought home a child. This demonstrates the un(der)valued nature of socially reproductive work and the subjugation of women, in this case, by the system. Furthermore, the women in this film are situated as subjects, with little agency in their personal lives and no agency in politics: everything seems to happen to them. The politics happens in the background to the ‘women’s issues’ in the foreground. This aligns with the production/reproduction divide, though has been criticised from a Third Cinema feminist perspective as stereotyping and essentially unhelpful.[32]

However, the similarities between these two protagonists end there. Class, and ethnicity as a factor of class in this film, heavily influences the outcomes of these women, also in relation to each other. Despite their commonalities, it is class and the employer-employee relationship that allows the exploitation of Cleo’s care work – demonstrated by the drama over the holidays, the shopping trip and labour, and work on vacation. Her rights as a worker are violated on the basis of her work being seen as ‘a labour of love’[33] and vital to life, which subverts Cleo’s rights as a citizen and worker. The paradox of ‘family’ is present throughout the film – and the family could be understood as a vessel of representation or political agency, which again is subverted at the will of her employers.

What the film presents, then, is a story about the struggles of claiming rights by isolated, marginalised individuals and the (intersectional) identities they represent. As women, Sofía and Cleo rely on each other and the support of other women to find a way through their struggles: they perform their citizenship and claim their rights. Despite the vulnerabilities, their agency is not compromised to the extent they cannot survive as citizens in a patriarchal setting. Cleo, however, as a working class woman of colour in an isolated work position, does not have the community around her to perform citizenship as Isin describes, and thus is too vulnerable with too little agency to claim the work and living rights that a citizen deserves. Instead, Cleo is resigned to stay within the family structure that both supports and confines her.

Conclusion

Films like Roma operate to visualise, familiarise, and make accessible through entertainment, the more complex sides of care work and intersectionality in the 21st century, despite being set decades ago. The themes addressed in this research included the representations and limitations of performative citizenship: at its core, it relies on group formation around a ‘common something’ as well as the security and agency to claim rights. The lens of social reproduction theory helps to clarify the contradictions and complexities of ‘work’ in a capitalist system, and looking at Roma in this way uncovered the factors that limit active performances citizenship. An intersectionality approach to the film likewise contributed to understanding where gains and solidarity can be found, but also where and why it could be missing. There is a plethora of ways that literary works like Cuarón’s Roma could be further analysed, with particular note to a postcolonial perspective that was not taken in this research, or a more engagement with the symbols and motifs related to masculinity and violence. There is are many thinking tools in fiction that can be used to learn about our social and political reality, so the work is not done yet. Especially today, as visual media grows exponentially as a main form entertainment, films and series can provide unique insights on topics of care, work, and citizenship in the future.

Endnotes

[1] Natalie Burclaff, ‘Missing Women and Feminist Economics | Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business’, webpage, 22 March 2021, //blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2021/03/missing-women-and-feminist-economics/.

[2] Burclaff.

[3] Megha Amrith and Nina Sahraoui, Gender, Work and Migration: Agency in Gendered Labour Settings (Routledge, 2018).

[4] Katherine Ravenswood and Raymond Markey, ‘Gender and Voice in Aged Care: Embeddedness and Institutional Forces’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29, no. 5 (9 March 2018): 725–45, https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1277367.

[5] Amrith and Sahraoui, Gender, Work and Migration., pp. 1.

[6] John D. Lindberg, ‘Literature and Politics’, Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association 22, no. 4 (1968): 163–67, https://doi.org/10.1353/rmr.1968.0019.

[7] Tithi Bhattacharya, ‘Introduction’, in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression (London: Pluto Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vz494j.

[8] Bhattacharya. 2-3.

[9] Bhattacharya. 4.

[10] Carmen Teeple Hopkins, ‘Mostly Work, Little Play: Social Reproduction, Migration, and Paid Domestic Work in Montreal’, in Social Reproduction Theory, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya, Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression (Pluto Press, 2017), 131–47, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vz494j.11. 136.

[11] Hopkins. 138.

[12] Engin Isin, ‘Performative Citizenship’, in The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, ed. Ayelet Shachar et al. (Oxford University Press, 2017), 499–523, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198805854.013.22. 500.

[13] Kathy Davis, ‘Intersectionality as Critical Methodology: Mit Einer Einleitung Zum Beitrag von Tina Spies Und Elisabeth Tuider’, in Postmigrantisch Gelesen(transcript Verlag, 2020), 109–26, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839447284-007.

[14] Davis. 111.

[15] Nira Yuval‐Davis, ‘Intersectionality, Citizenship and Contemporary Politics of Belonging’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 10, no. 4 (December 2007): 561–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230701660220. 566.

[16] Isin, ‘Performative Citizenship’. 501.

[17] Alessandro Pratesi, ‘Emotional Stratification, Social Inclusion and Citizenship’, in Doing Care, Doing Citizenship : Towards a Micro-Situated and Emotion-Based Model of Social Inclusion, ed. Alessandro Pratesi (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 197–219, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63109-7_8. 26.

[18] ‘Roma Awards and Nominations’, IMDb, 2022, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt6155172/awards/.

[19] Brooks Barnes, ‘Just Who Has Seen “Roma”? Netflix Offers Clues’, The New York Times, 6 February 2019, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/business/media/roma-netflix-viewers.html.

[20] Celia Hunt, Transformative Learning Through Creative Life Writing: Exploring the Self in the Learning Process (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/rug/detail.action?docID=1244547. IX.

[21] Tereza María Spyer Dulci and Alfredo Nava Sánchez, ‘Una Discusión Sobre El Racismo y El Trabajo Doméstico En Roma, de Alfonso Cuarón’, Diálogo 23, no. 1 (2020): 55–67, https://doi.org/10.1353/dlg.2020.0006.

[22] Katie Goh, ‘This Woman’s Work: Water and Labour in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma’, Girls on Tops, 21 December 2018, https://www.girlsontopstees.com/read-me/2018/12/21/this-womans-work-water-and-labour-in-alfonso-cuarns-roma.

[23] Andrzej Kulczycki, ‘The Abortion Debate in Mexico: Realities and Stalled Policy Reform’, Bulletin of Latin American Research 26, no. 1 (2007): 50–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2007.00213.x.

[24] Roma, Motion pictures, Drama (Netflix, 2018), https://www.netflix.com/watch/80240715. 54:38.

[25] Roma. 59:28

[26] Ewa Mazierska, ‘Class, Gender and Ethnicity in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma’, in Third Cinema, World Cinema and Marxism, ed. Ewa Mazierska and Lars Kristensen, 1st ed. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 255–73, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501348303.

[27] Roma. 1:33:46

[28] Kate Doyle, ‘The Corpus Christi Massacre: Mexico’s Attack on Its Student Movement, June 10, 1971’ (George Washington University National Security Archive, 10 June 2003), https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB91/.

[29] Roma. 1:51:01.

[30] Roma. 1:31:33.

[31] Roma. 2:03:17

[32] Mazierska, ‘Class, Gender and Ethnicity in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma’.

[33] Pratesi, ‘Emotional Stratification, Social Inclusion and Citizenship’. 25.

References

Amrith, Megha, and Nina Sahraoui. Gender, Work and Migration: Agency in Gendered Labour Settings. Routledge, 2018.

Barnes, Brooks. ‘Just Who Has Seen “Roma”? Netflix Offers Clues’. The New York Times, 6 February 2019, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/business/media/roma-netflix-viewers.html.

Bhattacharya, Tithi. ‘Introduction’. In Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. London: Pluto Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vz494j.

Burclaff, Natalie. ‘Missing Women and Feminist Economics | Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business’. Webpage, 22 March 2021. //blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2021/03/missing-women-and-feminist-economics/.

Davis, Kathy. ‘Intersectionality as Critical Methodology: Mit Einer Einleitung Zum Beitrag von Tina Spies Und Elisabeth Tuider’. In Postmigrantisch Gelesen, 109–26. transcript Verlag, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839447284-007.

Doyle, Kate. ‘The Corpus Christi Massacre: Mexico’s Attack on Its Student Movement, June 10, 1971’. George Washington University National Security Archive, 10 June 2003. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB91/.

Dulci, Tereza María Spyer, and Alfredo Nava Sánchez. ‘Una Discusión Sobre El Racismo y El Trabajo Doméstico En Roma, de Alfonso Cuarón’. Diálogo23, no. 1 (2020): 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1353/dlg.2020.0006.

Goh, Katie. ‘This Woman’s Work: Water and Labour in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma’. Girls on Tops, 21 December 2018. https://www.girlsontopstees.com/read-me/2018/12/21/this-womans-work-water-and-labour-in-alfonso-cuarns-roma.

Hopkins, Carmen Teeple. ‘Mostly Work, Little Play: Social Reproduction, Migration, and Paid Domestic Work in Montreal’. In Social Reproduction Theory, edited by Tithi Bhattacharya, 131–47. Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. Pluto Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vz494j.11.

Hunt, Celia. Transformative Learning Through Creative Life Writing: Exploring the Self in the Learning Process. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/rug/detail.action?docID=1244547.

Isin, Engin. ‘Performative Citizenship’. In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited by Ayelet Shachar, Rainer Bauböck, Irene Bloemraad, and Maarten Vink, 499–523. Oxford University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198805854.013.22.

Kulczycki, Andrzej. ‘The Abortion Debate in Mexico: Realities and Stalled Policy Reform’. Bulletin of Latin American Research 26, no. 1 (2007): 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2007.00213.x.

Lindberg, John D. ‘Literature and Politics’. Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association 22, no. 4 (1968): 163–67. https://doi.org/10.1353/rmr.1968.0019.

Mazierska, Ewa. ‘Class, Gender and Ethnicity in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma’. In Third Cinema, World Cinema and Marxism, edited by Ewa Mazierska and Lars Kristensen, 1st ed., 255–73. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501348303.

Pratesi, Alessandro. ‘Emotional Stratification, Social Inclusion and Citizenship’. In Doing Care, Doing Citizenship : Towards a Micro-Situated and Emotion-Based Model of Social Inclusion, edited by Alessandro Pratesi, 197–219. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63109-7_8.

Ravenswood, Katherine, and Raymond Markey. ‘Gender and Voice in Aged Care: Embeddedness and Institutional Forces’. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29, no. 5 (9 March 2018): 725–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1277367.

Roma. Motion pictures, Drama. Netflix, 2018. https://www.netflix.com/watch/80240715.

IMDb. ‘Roma Awards and Nominations’, 2022. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt6155172/awards/.

Yuval‐Davis, Nira. ‘Intersectionality, Citizenship and Contemporary Politics of Belonging’. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 10, no. 4 (December 2007): 561–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230701660220.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Cuarón’s Roma – 52:56

Appendix 2: Cuarón’s Roma – 55:54

Appendix 3: Cuarón’s Roma – 1:15:44

Appendix 4: Cuarón’s Roma – 1:08:42

Appendix 5: Cuaron’s Roma – 01:35:22

Appendix 6: Cuarón’s Roma – 2:03:36

discussion

feedback & thoughts

Official feedback: thanks for your paper on the film Roma, analysed through the lens of Social reproduction theory and performative citizenship.

I can very well see how these concepts relate in a meaningful way with the film and that they invite an insightful close-reading of the film as text.

Overall, you write well, the text is clearly structured. Beware (in a few occassions) of sentences where the subject if the sentence is not quite clear. Also, when writing about the film, make sure that you explain what is happening (i.e. summarize) for the benefit of the reader (don’t assume that they know the text).

In attachment a few more handwritten notes/comments.

Bibliography is neat, thanks!

Points to think about:

- how does the proposed theoretical framework help us to make sense of an identified problem or issue (that comes from the state of the art)? The topic is not necessarily same as issue/problem. It might help to think what the ‘goal’ or aim of the paper is.

- Concepts need to be explained carefully (such as performative citizenship) and their position (either as part of the problem, or as part of the instruments to resovle the problem) need to be made evident. Performative citizenship (how and why is it such a deviation from ‘traditional’ points of view?) mentioned in passing almost. Other concepts that are mentioned mostly in passing only are “Third Cinema feminst perspective”. Elaborate in smaller, more explicit steps what the film is saying about how rights are claimed? Which rights, and claimed how? (or failed to be claimed?). What exactly is the point of ‘democracy’ here (I see a link with the protest scenes, but perhaps a bit too much for your analysis here?)

- Be careful not to reproduce the language that you are critical of (why maid, and not domestic worker, for example?)

- Scholarship on representation of domestic workers? (especially in non-Western contexts - such as Mexico, or other Latin American contexts?)

- Water as theme is intriguing, but I wonder if it is ‘water’ as meaningful element/theme that should be considered, or rather something else that manifest in these scenes around water? (the link between ‘water’ and SRT remains a bit opaque).

- Distinction : working from home (many parents/women had to juggle care and paid-work at home during pandemic) vs invisible labour in the home (unpaid care work)?

- The “life-writing” aspect of the film doesn’t really seem relevant or necessary for your argument. Same with emphasis on ‘impact’: hardly necessary. What is interesting is how a problem is made sense of in the film (how meaning around the problem is construed).

- At end of introduction: don’t just explain the parts that are to follow, but provide in summary here your ‘intervention’: what will your argument be? (Which concepts, what questions for analysis, and what is it that you will show, claim, at the end?)

- Relationships between the women (in lieu of absence of the men) is also interesting: how these seem to cut across certain barriers, but also resist to cut across some others. How does ‘care’ and sisterhood work together in such contexts of inequality? (This is less about SRT then, and citizenship - rather more about how and where women meet or fail to meet each other as supporters/adversaries, etc.)

- What scholarship on this film is there, what has been the critical reception of the film? (The Box office and prize winning is interesting, but critical appraisal - reviews by professionals and scholars - also important to take note of. How does your own analysis relate to this conversation that’s already going on about this film?)

- What does the ‘water shortage’ aspect say in relation to SRT?

- In sectioin “water spilled”: be careful not to ‘asume’ something (such as what is ‘normal’ between employers and employees; the domestic employment situation is already quite different from regular relations, often times not regulated by contracts, regulations, etc. Here the aspect of “like family” becomes indeed an important and potentially very useful lens).

Whew. This was a big task. I'm not dissapointed, and I really learnt A LOT from the research in this topic and on that note it was one of the more challenging pieces I've ever set out to write. The personal circumstances surrounding the seminar and the writing of this paper were pretty rough, which definitely impacts the way I felt when submitting this work, as well as how I feel about the feedback... in the sense that I don't care so much, actually, despite the depth and usefulness of the reply I got but rather I am just happy that this particular part of my programme is over... more depth another time.